Europa’s huge buried sea may be sodium-chloride salty, like the oceans of Earth.

The huge ocean sloshing beneath the ice shell of the Jupiter moon Europa may be intriguingly similar to the seas of Earth, a new study suggests.

Scientists have generally thought that sulfate salts dominate Europa’s subsurface ocean, which harbors about twice as much water as all of Earth’s seas put together. But the Hubble Space Telescope has detected the likely presence of sodium chloride (NaCl) on Europa’s frigid surface, the study reports.

The NaCl — the same stuff that makes up plain old table salt — is probably coming from the ocean, study team members said. And that’s pretty exciting, given that the saltiness of Earth’s oceans comes primarily from NaCl.

Related: Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter

“We do need to revisit our understanding of Europa’s surface composition, as well as its internal geochemistry,” lead author Samantha Trumbo, of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com.

“If this sodium chloride is really reflective of the internal composition, then [Europa’s ocean] might be more Earth-like than we used to think,” she added.

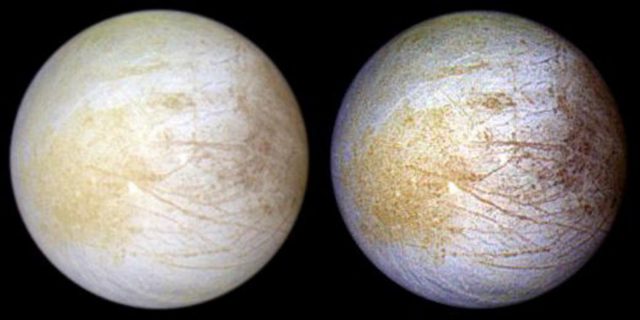

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 through 2003, spotted some odd, yellowish patches on Europa’s surface. Subsequently, laboratory experiments performed in simulated Europa surface conditions suggested that irradiated NaCl may be responsible for these “color centers.” (Europa lies within Jupiter’s powerful radiation belts, and the moon’s surface gets bombarded as a result.)

So, Trumbo and her colleagues went looking for signs of NaCl on Europa. They used Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) instrument over four observing runs, from May 2017 through August 2017.

STIS spotted an absorption line at 450 nanometers, which is characteristic of irradiated NaCl. But this signature wasn’t spread all over Europa. Rather, the team found it only on the moon’s leading hemisphere, the one that’s constantly facing Jupiter. (Like Earth’s own moon, Europa is tidally locked to its parent planet, always showing it the same face.)

In addition, the NaCl was concentrated in “chaos regions” — complex, disrupted and geologically young areas of the Europan surface where material may be welling up from the ocean below.

Europa’s trailing hemisphere gets hammered by sulfur compounds spewed out by another one of Jupiter’s many moons, the supervolcanic Io. But the leading hemisphere is shielded from this cosmic rain. So, the composition of the young, relatively pure leading-hemisphere chaos terrain “may best represent that of Europa’s endogenous material,” Trumbo and her colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online today (June 12) in the journal Science Advances.

However, it’s unclear if this is definitely the case, Trumbo stressed.

“We are confident that the sodium chloride is coming from the interior,” she said. “But the extrapolation to ‘the interior is chloride-dominated’ is less certain.”

For example, it’s still possible that sulfate salts — such as magnesium sulfate, commonly known as Epsom salt — rule the Europan seas, with NaCl as a relatively bit player. Indeed, experiments on Earth suggest that oceans such as Europa’s may start out sulfate-dominated; if you soak meteorites in water, sulfates leach out, Trumbo said.

The balance can tip toward NaCl over time, if certain geological processes prevail. For instance, extensive seafloor hydrothermal systems could do the trick. And Europa may well have such systems; they’re widespread throughout Earth’s oceans, after all, and also likely exist on the geyser-spewing Saturn moon Enceladus, another icy satellite with a subsurface sea.